Designing for Dialogue

Plot Twisters

-

Our online community, Plot Twisters, began organizing in early 2020 on Slack, sharing thoughts and resources about using technology to facilitate self-reflection and emotional literacy. Over the last two years, we have been creating an eponymous digital game world of playful self-awareness activities and wellbeing resources for ourselves and the general public. During our co-creation process we created a unique framework for self-governing our project: we began to use the very self-reflection practices we are inventing to communicate and negotiate values with each other.

We discovered that the lived experience of a community member, including their emotions, needs, and motivations, are valuable mechanisms for creating contracts and accountability processes. Many platforms lack collective institutional tools to emerge change and transformation from within the community (Schneider, 2020). Power is often incidentally distributed in a feudal hierarchy, in which one individual or a small group—the moderators—establish, modify, and enforce values for the whole community. Designing against implicit feudalism means intentionally creating conditions for dialogue (Freire, 1970): for members to advocate for their needs and organize structures to mutually fulfill them.

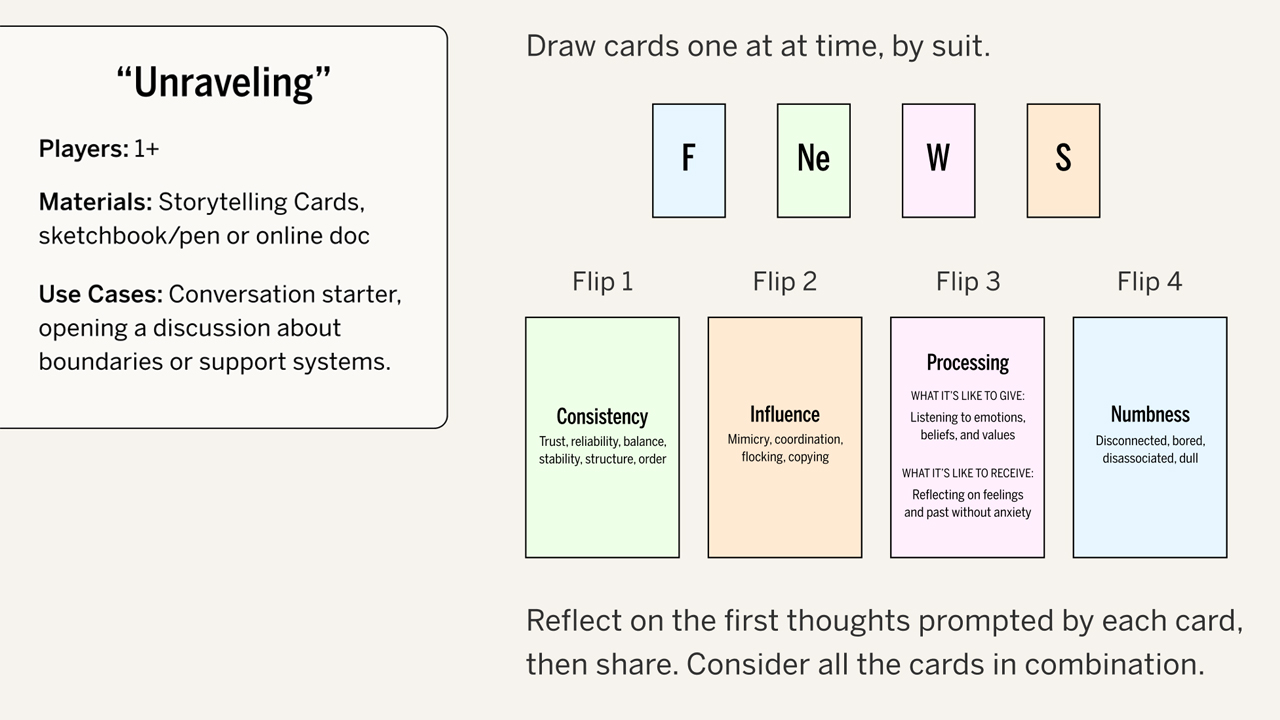

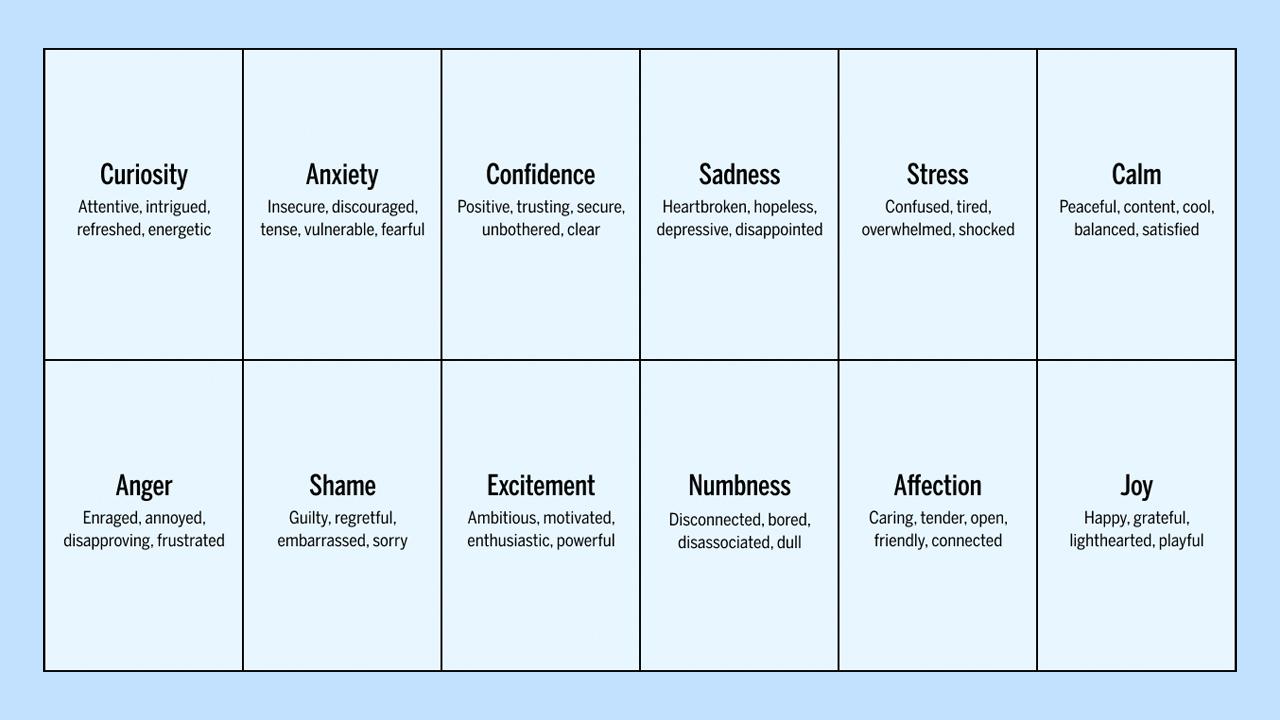

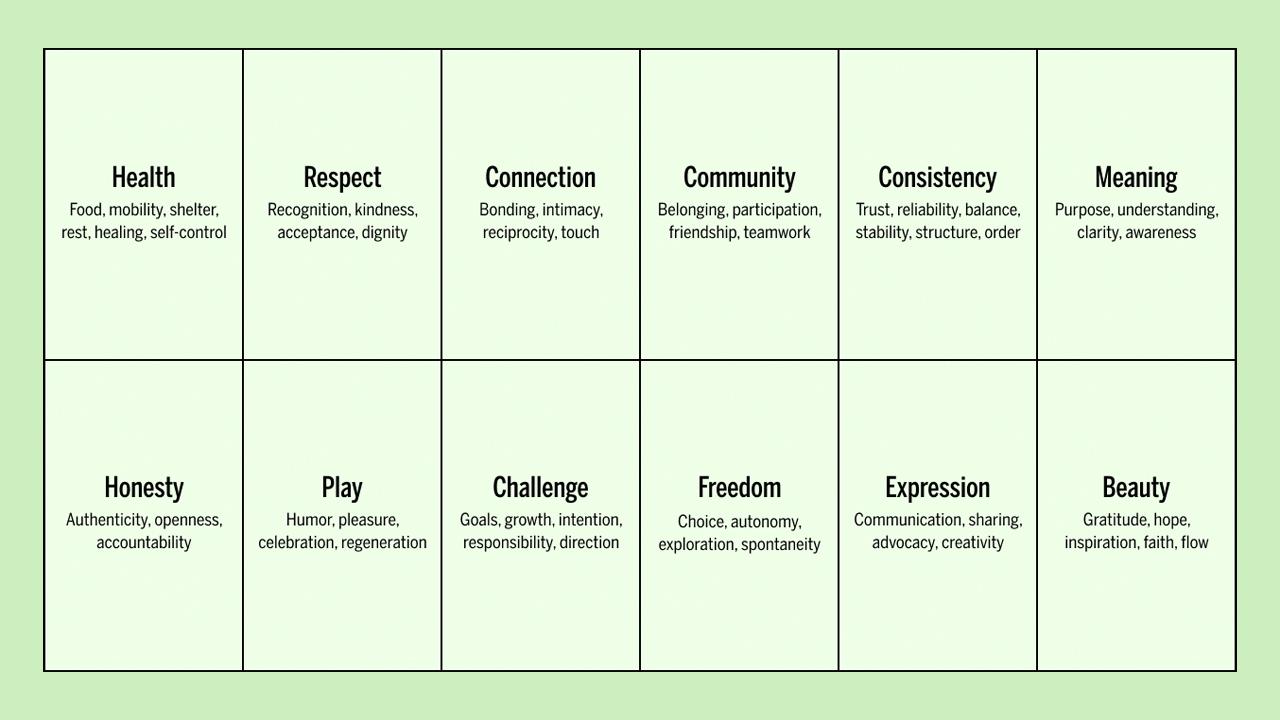

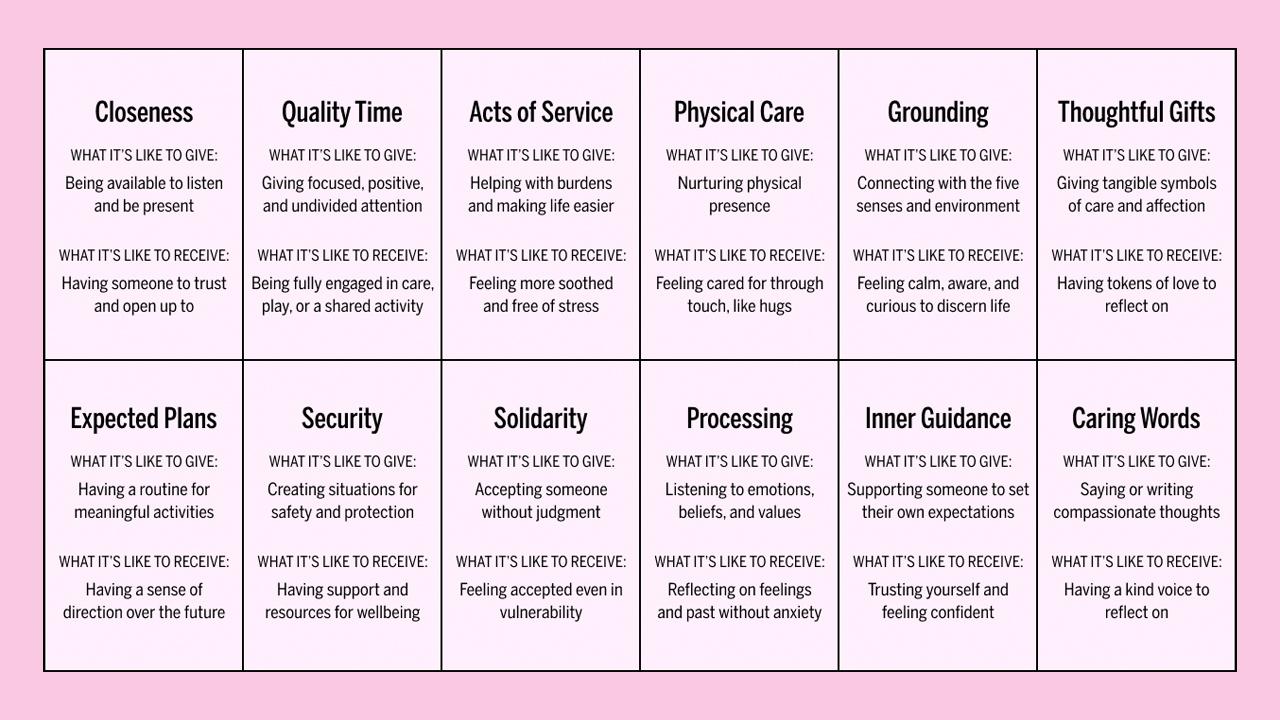

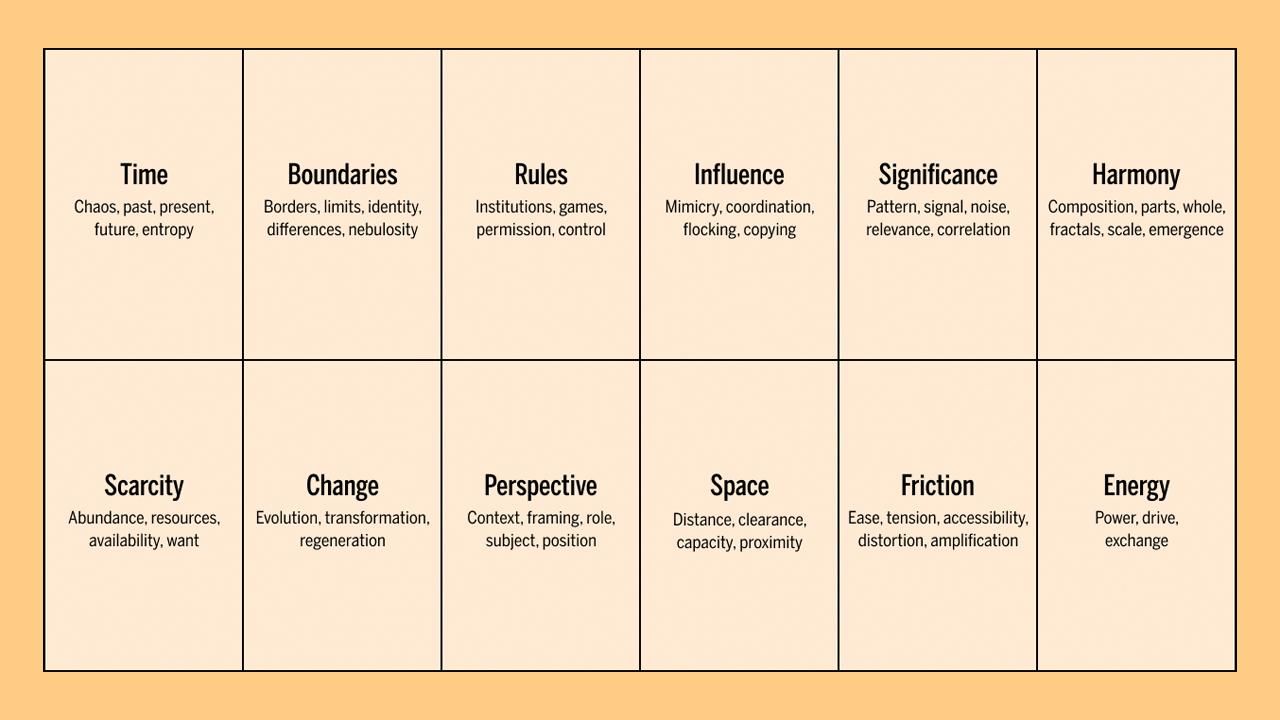

With the stewardship of the Governance Archaeology cohort, we formalized Plot Twisters’ implicit dialoguing practices into a tangible community framework and language for our game world, embodied by a deck of cards. The Plot Twisters Storytelling Cards (Figure 2) contain 48 cards divided into four suits: Feelings, Needs, Ways of Caring, and Structures. Our cards facilitate the exploration and expression of our values, as well as the setting of expectations based on those values. They support the process of building capability (McKercher, 2020), cultivating “we-ness” (Steinberg, 2004) and fostering proactive accountability (Kaba, Rice, and Sultan, 2020) prior to making serious commitments to shared projects, creative work, or resource exchange. The language could also be employed in a restorative or transformative justice practice to recognize and repair harm (Schoenebeck and Blackwell, 2021).

Playing with the Storytelling Cards can happen individually, one-to-one, or in groups, and can be used to journal, open challenging conversations, and facilitate community agreement workshops. But, like a standard deck of playing cards, we've designed these for players to come up with their own games and methods to use these cards to fulfill their individual needs. Dialogue can be documented and formalized as an ongoing record of roles, reminders, and boundaries, similar to what KA McKercher proposes in co-design as a “duty of care” (McKercher, 2020).

-

Introduction

When members of an online community encounter conflict, the default response is to exit due to the absence of basic democratic conditions (Schneider, 2020). Many platforms lack collective institutional tools to emerge change and transformation from within the community. Power is often incidentally distributed in a feudal hierarchy, in which one individual or a small group—the moderators—establish, modify, and enforce values for the whole community. This minority is judge, jury, and executioner in situations of accountability (Schoenebeck and Blackwell, 2021).

Designing against implicit feudalism means intentionally creating conditions for members to advocate for their needs and organize structures to mutually fulfill them. One lens to explore the ever-evolving endeavor of self-governance is what Paulo Freire (1970) describes as “dialogue,” or the process of co-creating reality. Freire explains that “the starting point for organizing the program of education or political action must be the present, existential, concrete situation, reflecting the aspirations of the people.” This paper argues that the lived experience of a community member, including their emotions, needs, and motivations, are valuable mechanisms for creating contracts and accountability processes.

To dive deeply into one example of dialogue as a mode of governance, we tell the story of our online community, Plot Twisters. Founded in 2020, Plot Twisters comprises 20+ researchers, designers, and technologists passionate about the power of technology to facilitate self-reflection and emotional literacy. Over the last two years, we have been creating an eponymous digital game world of playful self-awareness activities and wellbeing resources. Out of our co-creation process, a framework for fostering participatory governance emerged: we use the very self-reflection practices we invent to communicate and negotiate values with each other. To formalize the research context of our framework, select members of Plot Twisters participated as residents of the Governance Archaeology cohort in the Media Enterprise Design Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder. We employed media archaeology and a research-creation model to establish how feelings, exchanged in a visual and verbal format, can serve as democratic tools for discovering shared values and consensual institutions in digital relationships. This article introduces Plot Twisters’ community framework: our online governance structure and a prototype of our emotionally-literate communication toolset, presented as a deck of cards.

Conditions for dialogue: Freedom, play, and mutual aid

Plot Twisters began organizing in early 2020 on Slack, sharing thoughts and resources relevant to self-reflection across a handful of themed channels. Early discussions centered on the devaluation of wellbeing across existing educational and labor institutions, as most members recognized school as the first power structure that diminished their ability to make self-motivated decisions. As such, the first explicit value in the community was the freedom of all members to pursue their own interests at their own pace, in their own style.

Play, which was antithetical to experiences of traditional schooling, also became a guiding principle that helped us channel our intrinsic motivations. As low-stakes conversations in Slack evolved into robust creative collaborations with weekly meetings, members sought a way to communicate desires and plans. Defined as willful action motivated by the indulgence of curiosity (Schell, 2008), the value of play fostered conversations about consent. We used frameworks such as "yes, and" (Walsh et al., 2013) as a method to build upon each others' ideas, and this allowed each other to encourage trust, consensual creativity, and recognition of harm when it happens (Kaba et al., 2020). We were also inspired by the idea of “combinatorial play” in the process of creation, which emphasizes the permutations of possibilities that can emerge from exploring others' contexts (Calvino, 1987).

As team projects formed and grew, members started a ritual of checking in on each others' feelings. The research of Antonio Damasio in the Neurobiology of Human Values (2005) demonstrates that, no matter the individual’s cognitive ability, values emerge from the emotional and cognitive responses we have to social situations. As such, intimacy about our feelings became beneficial for a team’s ability to consensually play. Our practices look like what fellow cohort member Amelia Winger-Bearskin names “decentralized storytelling” (2021), or navigating one’s human experience in peer-to-peer story-spaces.

Building on our collective trust, we developed a practice of mutual aid. The mutual aid mindset involves harnessing the strengths of individuals in a collective; building a sense of “we-ness;” and using one’s own experiences for communal meaning making (Steinberg, 2004). In action, Dean Spade (2020) describes mutual aid as a form of participation where people care for one another while investing in the group. For Plot Twisters, valuing mutual aid allowed us to not only offer support to each other through psychological safety but also through resources, money, and emotional labor. This level of interaction helped foster bond based attachments which nurture stronger communities (Alberti, 2019), setting a precedent for self-organization of team strengths and self-determination toward solidarity.

Community design: Living in Twisterland as we build it

Plot Twisters was a centralized community by default because freedom, play, and mutual aid elevated the power of members who had the most time and resources to offer. This structure essentially resulted in an implicit “do-ocracy,” where select members had the most ability to “do.” The flaw with do-ocracies is that they may “fail to recognize that not everyone is equally equipped with the free time and other resources to participate” (Schneider, 2020). Members were interested in formally institutionalizing our overarching values, if not to distribute the authority, then to make the current distribution explicit and cohesive with how we saw ourselves: an organization antithetical to “relations of domination” (Freire, 1970).

Meanwhile, the community was developing components of the Plot Twisters game world. The game’s imaginary universe, called “Twisterland,” will be designed to be played in solo mode or social mode and house journaling minigames, identity building activities, and conversation starters guided by non-playing characters. We saw the link between our creative goal—to design a platform that embodied our values—and our pursuit of a transparent institution, and realized the best way to build our game world was to play it ourselves.

Figure 1. Prototype of the "Homeroom" in the Plot Twisters game world.

Members of Plot Twisters chose to build the Twisterland governance structure on two key methodologies: co-design (McKercher, 2020) and circles (Dana et al., 2021). Co-design provided specific guidelines for facilitating dialogue. Described by KA McKercher as the practice of “elevating the voices and contributions of people with lived experience,” co-design lists specific ways power may be imbalanced, from inherited privilege to extroversion, and how to build capability of all participants from different expertises and experiences. Circles structurally implemented co-design by trusting groups in a community to make decisions together through consent, and convening group representatives to advocate for specific interests (Dana et al., 2021). Together, co-design and circles form the institution of Plot Twisters membership and the groundwork for fostering freedom, play, mutual aid and decentralized storytelling (Winger-Bearskin, 2021).

Plot Twisters Storytelling Cards

With the stewardship of the Governance Archaeology cohort, we honed the main goals of our language. First, it must facilitate the exploration and expression of our values, as well as the setting of expectations based on those values. Next, our language must be flexible enough to be used for both preemptive and reactive intervention. As a process of building capability (McKercher, 2020), using the language could cultivate “we-ness” (Steinberg, 2004) and proactive accountability (Kaba, Rice, and Sultan, 2020) prior to making serious commitments to shared projects, creative work, or resource exchange. The language could also be employed in a restorative or transformative justice practice to repair harm; its vocabulary may empower people to communicate their feelings and strategies for healing, and their needs and structures for accountability (Schoenebeck and Blackwell, 2021).

To choose a tangible medium for conveying our language, we examined the affordances of existing self-reflection activities. The activities we loved most centered people with traumatic lived experiences and/or intersectional identities (Meenadchi, 2019; Ernst 2020). Structurally, we built on the cognitive science taxonomy of John Vervaeke (2013) and the categories in tarot. We also explored “values sensitive design approaches" (Friedman and Hendry, 2019) and were particularly inspired by “scenario co-creation cards,” a design research project about “[eliciting] values from people who may be in a power relationship that hinders directly discussing implicit values” (Alshehri et al., 2020). Scenario co-creation cards are self-contained and “enable non-linear progression and… comparisons and connections between different concepts.” Based on all of these inspirations, we have started prototyping a similar freeform card deck to introduce our language.

Figure 2. The full deck, separated by suit: Feelings (blue), Needs (green), Ways of Caring (pink), Structures (orange).

The Plot Twisters Storytelling Cards (Figure 2) contain 48 cards divided into four suits: Feelings, Needs, Ways of Caring, and Structures. Games and freeform play can be an individual, one-to-one, or group activity, and can be used to journal, open challenging conversations, and facilitate community agreement workshops. But, like a standard deck of playing cards, we've designed these for players to come up with their own games and methods to use these cards to fulfill their needs.

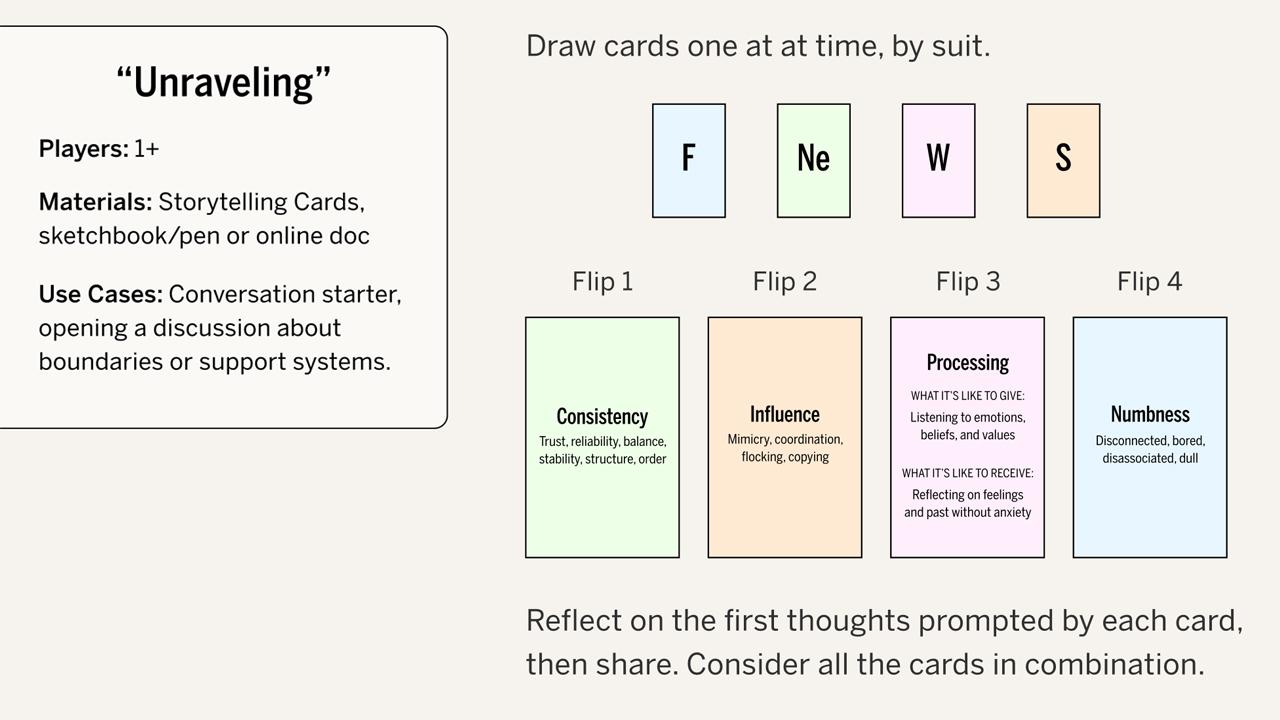

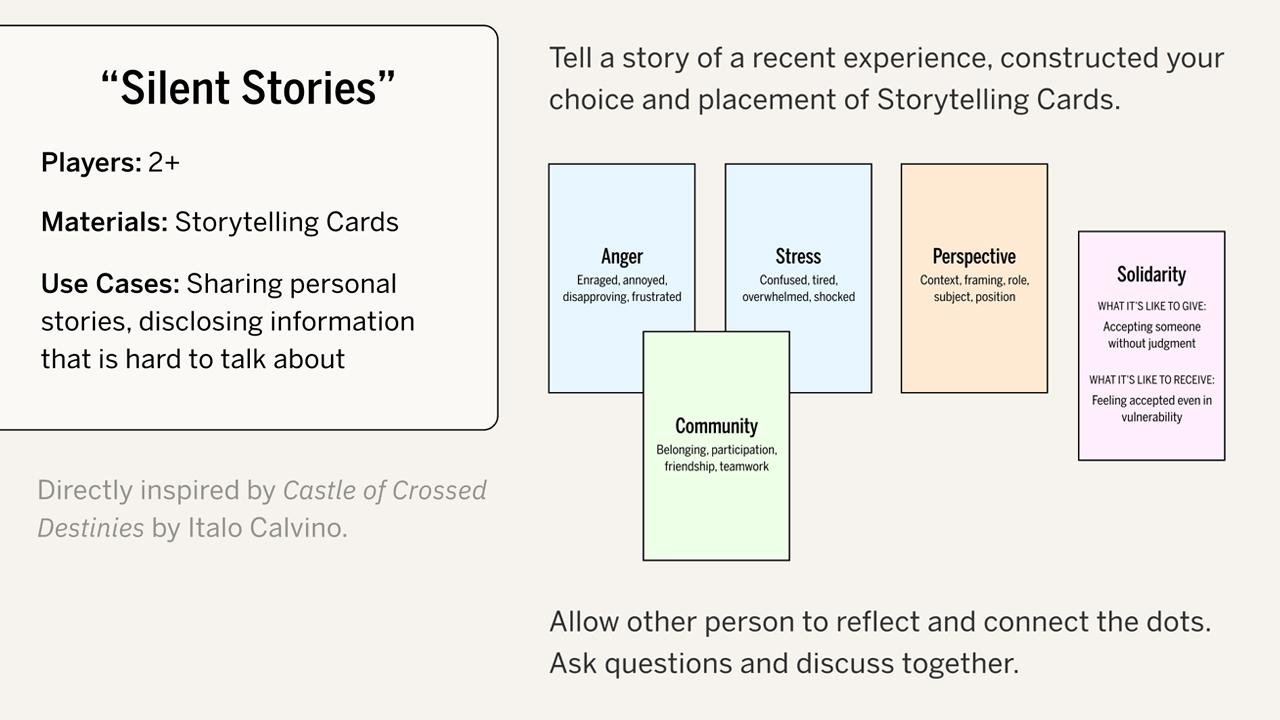

Figure 3. How to play two of our favorite games, "Unraveling" and "Silent Stories.”

Two games so far are called “Unraveling” and “Silent Stories”, the latter inspired by Italo Calvino's book The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973). During play, members are free to explore any narrative that arises while still using the taxonomy of the cards to convey meaning when necessary. All freeform plays affirm Calvino’s theory of storytelling as a cybernetic experience (Calvino, 1987). Players draw cards from the deck, reflect on experiences recalled from the combination drawn, express their feelings, and articulate tangible expectations based on their feelings. These expectations can be documented and serve as an ongoing record of roles, reminders, and boundaries, similar to what KA McKercher proposes in co-design as a “duty of care” (McKercher, 2020).

Conclusion: Digging for more dialogue

This paper celebrates nearly two years of learning firsthand, from first principles, how to run an organization that empowers wellbeing through communication. The Plot Twisters Storytelling Cards are a way to facilitate collective conversations about our lived experiences and the values we share.

But, the agency to play comes with the negotiation of expectations. Our next steps involve formalizing a "playbook" that explicates guidelines for safe and effective card gameplay, maps card games to conflict scenarios, and suggests methods for documenting duty of care contracts or mutual aid agreements from gameplay. This can parallel how stories in Indigenous story-spaces are woven together as wampum to protect and communicate a community’s shared values (Winger-Bearskin, 2021).

Plot Twisters exemplifies just one potential structure to mediate and nurture collective life. We are invested in a future where more communities view feelings as necessities for governance and accountability. As we continue building our world, we invite others to consider emotionally-aware dialogue as an instrumental tool for consent, democratic governance, and communal meaning.

References

Alberti, F. B. (2019). A biography of loneliness: The history of an emotion. Oxford University Press, USA.

Alshehri, T., Kirkham, R., & Olivier, P. (2020, April). Scenario co-creation cards: A culturally sensitive tool for eliciting values. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14).

Calvino, I. (1973). The Castle of Crossed Destinies.

Calvino, I. (1987). The Uses of Literature: Essays. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Damasio, A. (2005). The neurobiological grounding of human values. In Neurobiology of human values (pp. 47-56). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Dana, C., Hornbein D., Vincent, R., Schneider, N. (2021). Community Rules. Media Enterprise Design Lab.

Ernst, J. (2020). Routes of Safety. https://www.mswjake.com/resources

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Friedman, B., & Hendry, D. G. (2019). Value sensitive design: Shaping technology with moral imagination. MIT Press.

Kaba, M., Rice, J. D., Sultan, R. (2020). Uncaging Humanity: Rethinking Accountability in the Age of Abolition. Bitch Media (December 8, 2020).

Meenadchi. (2019). Decolonizing Non-Violent Communication. Co—Conspirator Press, Feminist Center for Creative Work.

McKercher, K. A. (2020). Beyond sticky notes. Doing co-design for Real: Mindsets, Methods, and Movements, 1st Edn. Sydney, NSW: Beyond Sticky Notes.

Schell, J. (2008). The Art of Game Design: A book of lenses. CRC press.

Schneider, N. (2021). Admins, mods, and benevolent dictators for life: The implicit feudalism of online communities. New Media & Society, 1461444820986553.

Schoenebeck, S., & Blackwell, L. (2021). Reimagining Social Media Governance: Harm, Accountability, and Repair. Schoenebeck, Sarita and Blackwell, Lindsay. Reimagining Social Media Governance: Harm, Accountability, and Repair (July 29, 2021).

Spade, D. (2020). Solidarity not charity: Mutual aid for mobilization and survival. Social Text, 38(1), 131-151.

Steinberg, D. M. (2004). The Mutual-aid Approach to Working with Groups: Helping People Help One Another. Routledge.

Tausczik, Y. R., Dabbish, L. A., & Kraut, R. E. (2014, February). Building loyalty to online communities through bond and identity-based attachment to sub-groups. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing (pp. 146-157).

Vervaeke, J., Lillicrap, T. P., & Richards, B. A. (2012). Relevance realization and the emerging framework in cognitive science. Journal of Logic and Computation, 22(1), 79-99.

Walsh, M., Roberts, I., & Besser, M. (2013). Upright Citizens Brigade comedy improvisation manual. Comedy Council of Nicea LLC.

Winger-Bearskin, A. (2021). Decentralized Storytelling. Co-Creation Studio at the MIT Open Documentary Lab.